Mastering Hammer & Chisel Tom Young On Stone Carving & Lettering

Tom Young’s home is like his work as a sculptor – hand designed and hand made. We enter at street level through a beaten-up door tucked beneath a fishmonger’s sign, step past a brick façade and into a world of chaos and creativity: a warm, insulated studio blanketed in the chalky residue of chiselled stone.

Beyond it are raw, untreated rooms packed with machinery and materials, all wrapping an internal courtyard – a human-sized terrarium where the really dirty work happens. On the day we visit, that’s where our current collaboration with him is taking shape - a commission working alongside castmaker Jak Blackman, to create a large 3D heraldic crest for a client's reception.

Asked to rethink a historic coat of arms as a contemporary centrepiece - this project saw us lift a design from paper and build it into a 2 m wide, 1.5 m proud reality. Every element was modelled in clay, before silicone moulds were taken and fibreglass casts produced. Finished by hand with opaque gouache paint and 24-carat gold leaf, the result is a bold and beautiful emblem, where heritage craft meets modern fabrication.

Through the glass, daylight floods the stairwell and spills across the steps to the upper floor, where the kitchen, sofa, balcony – and, most importantly, the record player – live. This is where we talk. Tom’s beard is glittering with gold dust, so it's a little bit magical.

It becomes apparent this self-build differs from the rest of Tom's esteemed portfolio – which includes stone carving and letter making commissions for St George’s Chapel, Windsor, The Old Royal Naval College, the Olympic Park and Eton College – in that the house is yet unfinished. It is one of his longer-term ambitions, often cast aside for the sake of his clients.

Nevertheless, it’s where the magic happens, though he would disagree. Tom wants to demystify the air around heritage skills. Like anything else, learning a traditional craft just takes practice, he says. And he would know, having trained at the City & Guilds of London Art School. He now teaches Lettering on the Historic Carving course, guiding the next generation how to design and carve lettering in stone.

Tell us a bit about what you do…

Primarily I’m a lettering designer working mainly in stone, so I make architectural lettering or memorial work, that kind of thing. I also work in other materials like wood and metal. Although this current heraldic project, making a large crest, doesn’t involve any of those materials or lettering, it does use a range of the skills that we normally use, just applied in a different way.

How do you choose who to collaborate with?

I usually work by myself, but yes, I often employ other people if I’m working on larger commissions. I know a lot of other lettercarvers through my teaching and through Letter Exchange, which is an organisation that promotes lettering across a broad range of disciplines. I usually work with former students on bigger commissions. There’s a big pool of talented alumni so it’s great to see the transition from the early days of being a student to working together on interesting projects. There are a couple of people who work with me quite regularly – Ayako Furuno and Jackie Blackman, who’s downstairs in the studio now

What's Jackie up to down there?

We modelled each element of the crest out of clay first and are now making moulds as we need four copies of the crest for different locations. Jackie is brilliant at mouldmaking and casting, so she has taken all the moulds from the clay and cast the four identical copies of the crest in fibreglass. It’s just one of the things she can do, but she’s a real expert in that department. It requires a real depth of study and knowledge and she’s brilliant, so I’m happy to step back and let her get on with it. We’ve done the finishing touches together with paints and gold leaf.

How did you come to specialise in stone lettering?

I was interested in doing graphic design, but I was also interested in making things by hand, and my education was a halfway house where I could do both. I went to a brilliant art school here in Kennington which I mentioned before, called the City and Guilds of London Art School.

I actually found out about it by chance. My then-girlfriend’s grandmother was a childhood friend of an amazing German letter carver called Ralph Beyer, who’d come to England in the late 1930s. Among other things, he’s known for carving the “Tablets of the word” in Coventry Cathedral. I met him and he was, at the time, teaching at City and Guilds and encouraged me to apply.

When I was there, there was a course that was purely focused on lettering. All of the related disciplines – calligraphy, stone carving, wood carving, glass engraving, gilding – were covered. It really was an amazing course. Unfortunately, it isn’t around anymore, but that’s where I teach now, on the Historic Carving course of which lettering is a component.

What do you enjoy more – teaching or doing?

What’s brilliant about the system at City and Guilds is that all of the teachers are practitioners, so it’s a part-time job for a day a week in term time. That means I’m not burnt out by it, so I look forward to it every time I go in. It’s an exciting dynamic and it’s full of potential. People changing their lives, going in to do something completely new. That’s pretty good!

Stone carving seems like quite a traditionalist craft, is there room to be contemporary?

If you’re talking about lettering work, commissions tend to be more traditional – an inscription for a building or a monument in the Capital. But outside of that, people are doing much more expressive stone carving work for themselves so yes, you definitely can be.

In the UK there is a tradition of carving that comes from the revival of hand lettering by Edward Johnston at the turn of the last century. Eric Gill learnt from him. And that absolute direct link of master and apprentice just carried on and on.

Eric Gill died in 1940, so you can imagine that there were still people alive at the end of the 20th century who had worked for him. Those direct links kept the tradition fairly intact. Now though, that chain is broken and once that happens, a craft can start to move a little bit more quickly. We’re maintaining a good grip on formal work, but becoming more expressive all the time. Letter Exchange is a great place to see these changes – there’s a season of talks every year where you can find out what people have been up to and a brilliant journal Forum that is full of all the latest work.

What is the joy of carving in stone for you?

It’s quite hard to describe. The finished carving is very different from a two-dimensional drawing. It’s all about how light interacts with the letters that you’ve made. It’s a magical transformation from lines on a flat surface to a dynamic three-dimensional object.

Lettering is something that we are surrounded by all the time, but if you ask people to draw letters, it’s difficult to do because the letters have a structure that needs to be understood before they start to work well.

Is there anything specific to watch out for with this material?

Stone is a natural material so it can be unpredictable; something unexpected can be lurking in the middle of it, so you can find that you’ve hit something you didn’t think you were going to hit and bits end up falling off. It does happen, but less and less as you build up experience with different types of stone. You need to wear a mask to carve some types of stone as the dust can be full of silica , which is very bad for your lungs.

Could you tell us a little about lettering and the creative process?

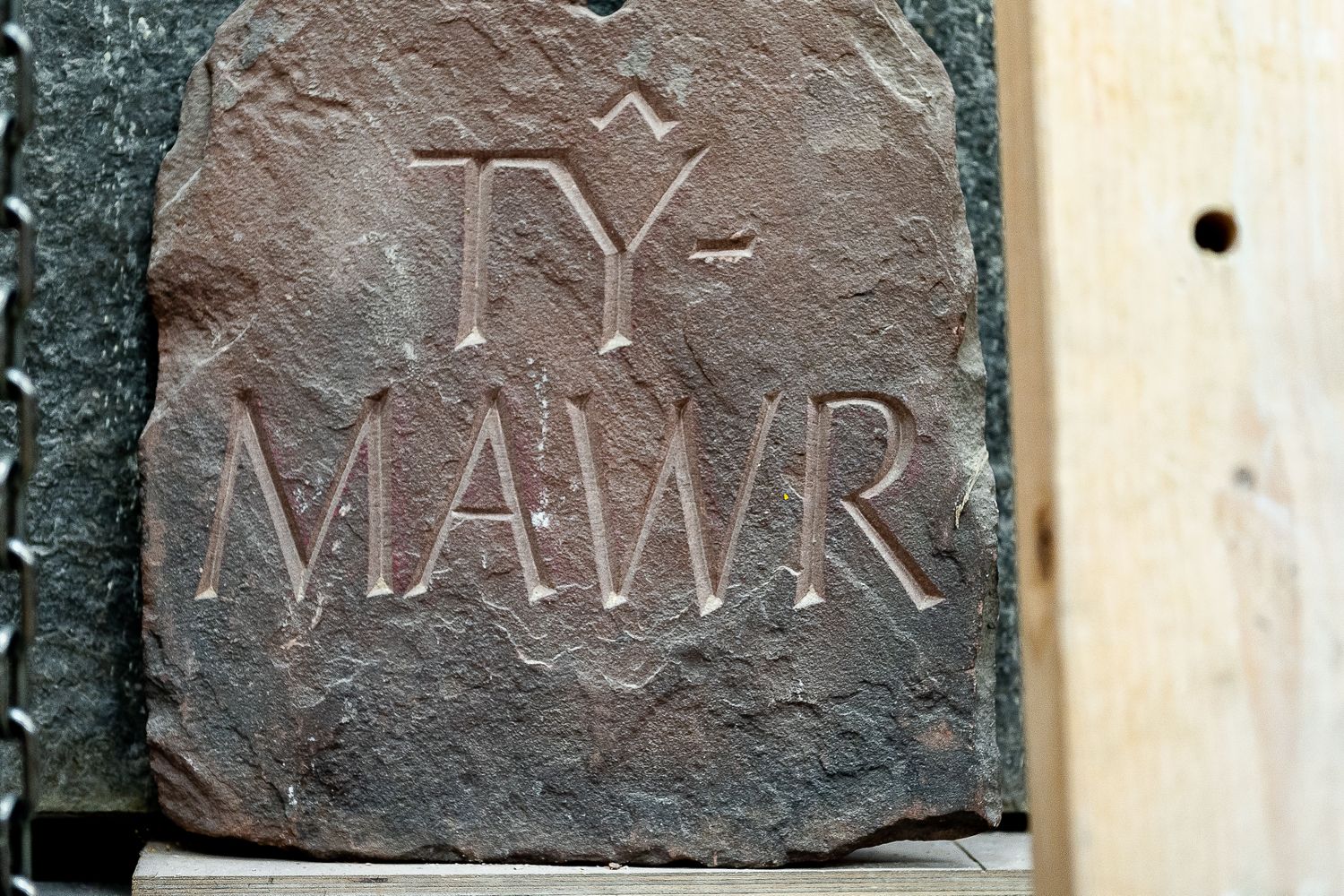

The first thing is to meet with the client and, ideally, visit where the work is going to be installed. It makes a huge difference to look at the setting in real life, as decisions about the size of the finished object and choice of material are crucial. Following that visit and a discussion of the stone, I’ll make small sketches to try to get a sense of what I want to do with the design. Once I’m happy with that, I’ll make a fairly neat scale version to send to the client. This can then start a discussion about the design and there might be some adjustments to make, but once the client is happy I’ll start working at full size. There can still be quite a lot of work do to get to the right forms, but the scale drawing gives a good idea of how everything will work together.

It’s important to draw the whole inscription – I want to keep the slight variation in letters, even in a formal inscription, or else the end result will always look a little lifeless. Once everything is drawn, I’ll use Photoshop to make final adjustments to the spacing.

I prefer to order stone that’s roughly sawn because I enjoy the process of shaping it myself. I would much rather have some kind of interaction with it as a sculptural object. It makes it more satisfying for me and feels like more of a complete process.

Once I’ve shaped the stone, I transfer the drawing onto the stone and make a start on the carving.

Any rituals that help you start working?

No, nothing like that. There doesn’t need to be a whole ritual before you can pick up a chisel.I think of being creative as a practical thing. I don’t want to idealise it.

I want more people to do this, I don’t want people to think it’s unachievable. I would much rather people realise that you have to get your hands dirty. And you just have to do a lot of it if you want to get good at it. You don’t have to dress in a certain way or keep your studio in a particular way. You can start with nothing, start on a very low level and build up. And there’s very little equipment required to do some of these things.

How long did it take to get to where you are?

It took a long time, and I still look back at work that I did a few years ago and think “I could have done that differently”. I think if you ever feel like you’re putting perfect work out then you should probably stop – there’d be nowhere to go. You always need challenges.

Even if you’re doing formal work there’s still plenty of room for variation- you can get excited about even the smallest elements of a design; you may have never covered that ground before. All manner of different things could happen, nothing is consistent. Clients often react unexpectedly to something I’ve designed, or sometimes the stone itself behaves unpredictably.

Are you working on your house at the same time?

Yes, if I’m not doing work, I’ll be trying to finish something or make something for the house. I really enjoy that. You know, that’s my passion for processes. If you enjoy learning new skills you find that a lot of the things you’d done for fun come together and at some point inform your work. Like with this project casting a crest – you feel like you can take on things that you might just normally have assumed you couldn’t do. Then you bring in other people who have their own areas of expertise, and learn even more from them.

Has putting your studio in your home impacted your work/life balance?

I built the house with a studio in it because I’ve always got lots of things going on with the kids, so this way I can borrow time here and there to complete projects – I try and be quite disciplined, but I have the option of working in the evenings to get things done. If I had to stick rigidly to the conditions of a nine to five in a workshop, I think I would struggle. If you’re doing any of these kinds of making, you’re never 100% sure what’s going to happen on any given project, so it’s quite good to have flexibility. In some ways it’s not great, because unless you’re quite careful, you can become a bit isolated working by yourself at home.

How do you avoid feeling alone at work?

Ayako does her own work here and also helps me out on various projects, so I’m rarely working by myself. My work at City and Guilds is a really good opportunity to get out and interact with other people and Letter Exchange is another great way to make connections.

Top three favourite things to listen to?

It depends on what I’m doing. My ever-growing charity shop record collection is pretty good, so if I’m upstairs with the record player, I would definitely be listening to an album that I’ve found in a charity shop or online. Radio 6, Radio 4, that kind of thing. Ayako and I listen to a lot of brilliant podcasts. There are so many good ones, like Serial. There was one that was fantastic and I was absolutely gripped by it, about the Black Dahlia, called Root of Evil. It is the most astonishing story.

Were you always creative?

There was a lot of creativity at home when I was growing up. My dad made things for the house and did a lot of painting and printmaking after he retired. Mum ran a dance school for more than 30 years and is also an accomplished potter and sculptor.

I loved printmaking at school and started using tools at home from quite an early age. There was always lots of that kind of stuff going on. It was easy – you know – I didn’t have to persuade my parents that doing something slightly unusual was a good idea.

Was it a difficult journey, is it a difficult journey?

It hasn’t always been easy, but people are coming to value these skills more and more. There’s a rediscovery of making across the board. I’ve seen a huge range of people who have pulled away from what they were doing and are just drawn to do these things. It absolutely resonates with them, it’s instinctive, it’s an exciting time to be making things.