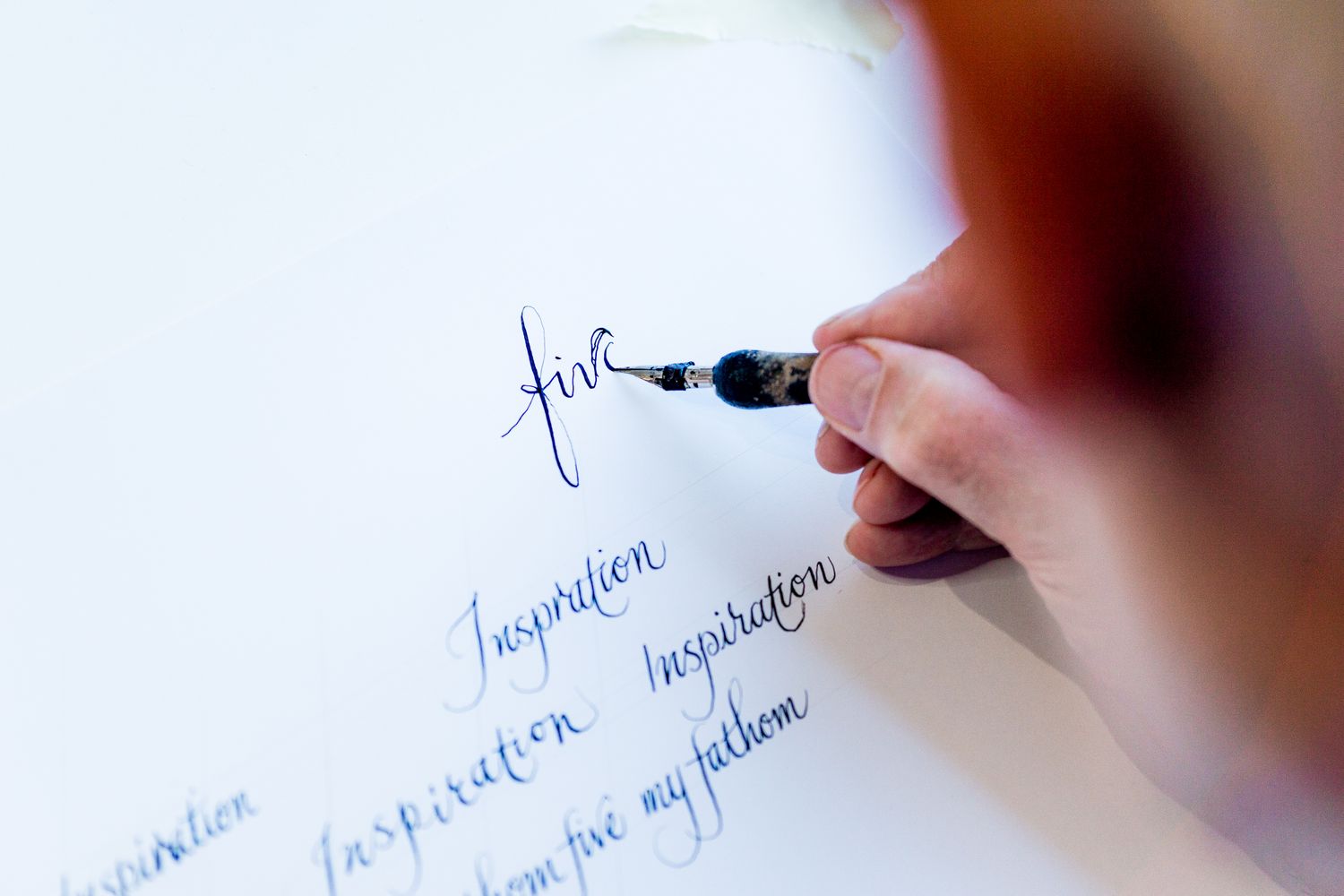

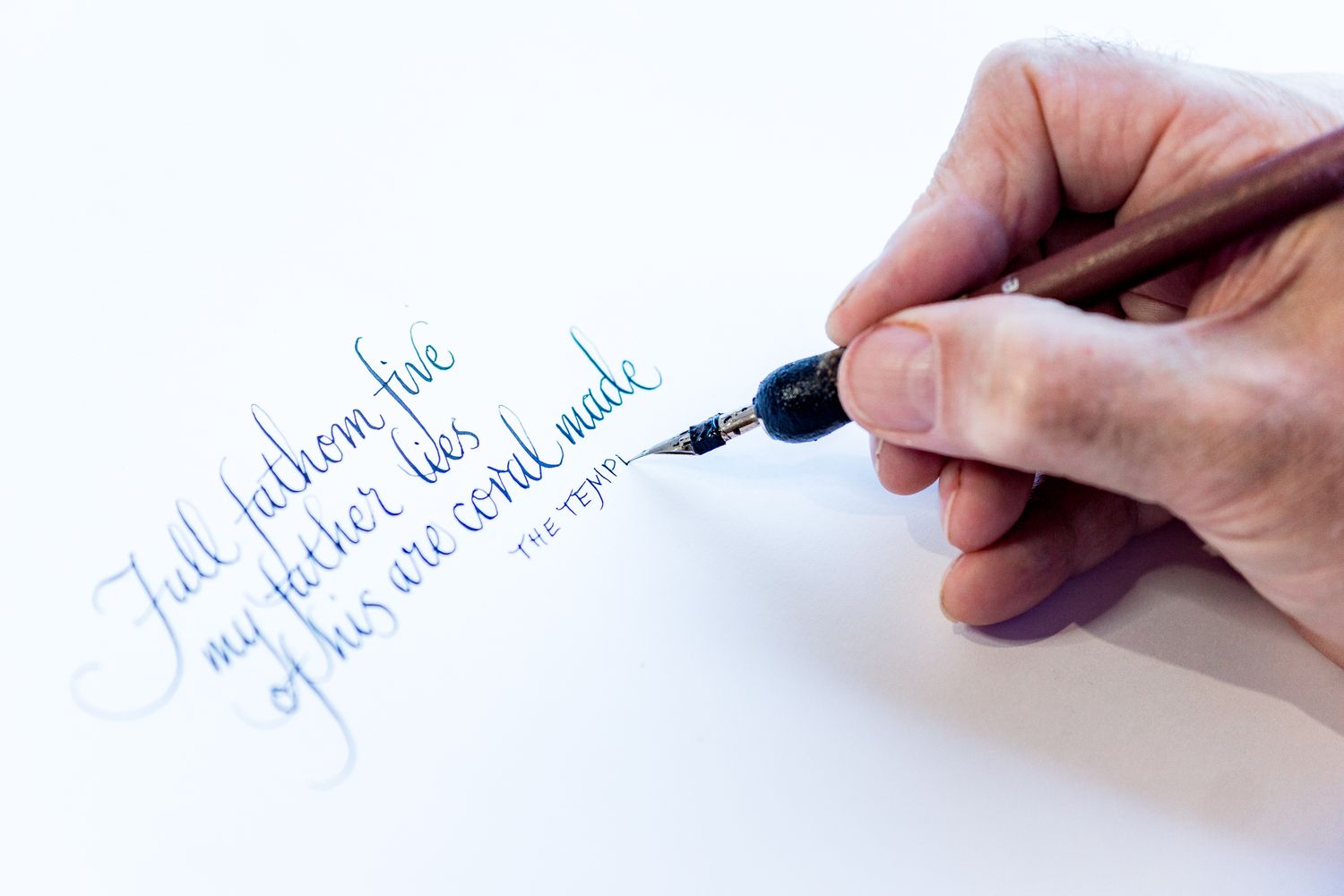

Rewriting The Script Brian Heppell, On His Love For Calligraphy

Brian Heppell’s life has flowed from one loop to another much like the ink from a writer’s pen: he’s transformed from an apprentice typesetter at The Times to an entrepreneur running his own London sign makers’ shop and vintage lettering business , to a post-retirement career in calligraphy.

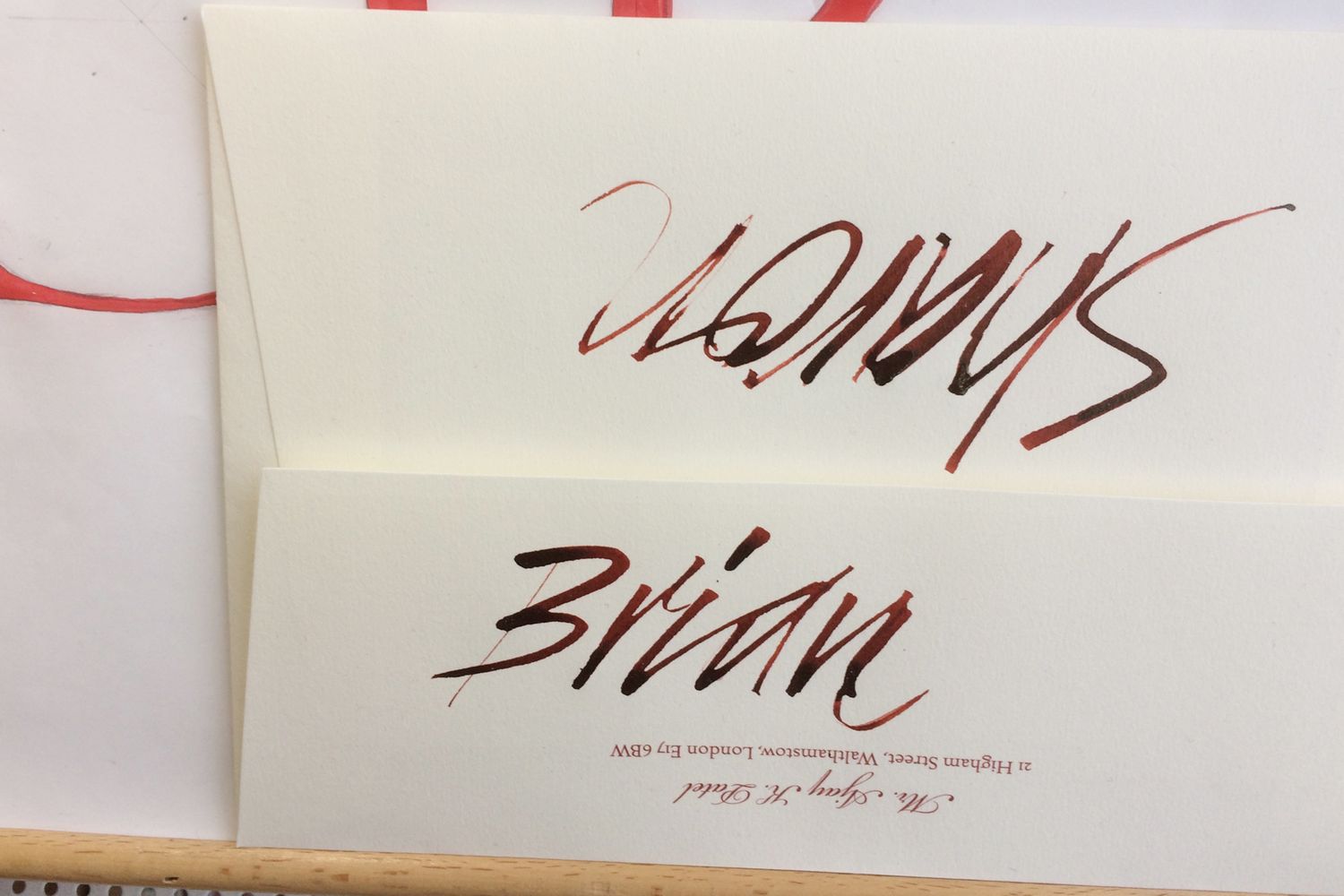

With his wife Sharon by his side, he talks us through the twists, flicks and twirls of his vocation, and shares his thoughts on creativity…

What’s the first thing you ever made?

Brian: We really didn’t have money to afford to buy pencils and paper but I probably did bits of drawing, it was just aeroplanes and searchlights because I was born in the war time. It was quite hard.

Sharon: Yes when we were young, we were writing with pencils, or a slate. We used to have slates, didn’t we?

Brian: I don’t suppose we had a pen until we got to the junior school. Yes we didn’t have ball point pens, did we? It was always you dip pens at school.

Sharon: We had to use ink. And then, you can imagine trying to do exams. You’re doing your ‘A-Levels’, and you’re having to write with ink and your hands are sort of smudging.

Brian: Your fingers were always with black ink on them. One of us always had to be the ink monitor, who would go around filling inkwells up for the other kids.

How was your handwriting then?

Brian: I don’t remember any formal handwriting being taught to me until by end of school. I think you looked at what your mum and dad had done, and copied your mum and dad’s writing. I don’t think my handwriting was particularly attractive – it was just typical of those days, you’d just make sure you’d loop your letters together.

Sharon says to me, “You find it easy just to pick up a pen.” Well, I don’t really think about what I’m going to write, sometimes it’s just a load of garbage. It’s only just linking letters together, and then, trying to think how creative could I make that.

Are people born with a talent?

Brian: I often think on that. I think everybody’s born with something like that, aren’t they? They’re either mathematically-minded, or mechanically-minded. Or they’re either artistically-minded, or humanitarians in some way. I’ve had people say to me “Oh, God. I’ve been doing this all my life, and I bloody hate it!” And you think what are you doing it for? How horrible is that? So I always say to kids, if you don’t like what you’re doing, get out of it. Don’t get out of a job though until you’ve got a job to go to, but always try to go where your desires are leading you.

Was anyone in your personal history influential in making you the creative that you are?

Brian: There was no art on my side whatsoever but I always thought they were okay with me doing it, they left me alone. I was kind of trusted to do whatever I did, so I’d be out and about, I used to go on bloody great long journeys, and I had no idea where I was going to – just had to get a train and work out how to get there. I was only tiny. Nine? Eight? I was very young. Oh, yes, I was trusted completely really, but I trusted others – I was confident enough to get on a train and know I’ve only got to ask somebody, and I was never shy in talking to people, where there’s always that fear now. So I think that trust they gave me, gave me self-assurance.

Where do you get your inspiration?

Brian: I’m always looking at posters. It could be anything, even the Waitrose magazine or a bit of packaging, packets and tins – because really, if you go along to a supermarket, you’ve virtually got a type library in front of you. For me it’s not just calligraphy, it’s the whole lettering aspect.

The first thing I did when I left school is I took a typewriting course. Now, I wasn’t going to be a secretary. I don’t know why I did a typewriting course. But, in actual fact, it was good for me getting to know the keyboard, because I ended up by being a keyboard operator on a typesetting machine. I got a job at The Times newspaper, so right away I was involved with print. They sent me to print school, and I kind of think my handwriting started to develop up from there – not that I was taught calligraphy, I just made a point of making my handwriting look better. You could see a definite change, and I got from school boy-ish to a certain level.

Was that when you really discovered that type and letters are something you wanted to work with?

Brian: Yes so I had a lucky break. One of my school friends had a father who worked at The Times newspaper in London and his Dad had lined him up for a job there. My friend asked his Dad if he could get me a job there too and – to my surprise – I was given an interview and offered a job, and later on an apprenticeship to become a hot metal typesetter or compositor. It was a bit of closed shop in the newspaper world in those days, you usually had to be related to someone who worked on the paper in order to get in.

So I was trained in-house by The Times. Then I was also trained to be a Monotype keyboard operator later at The Monotype School in Cursitor Street, London, just off Fleet Street – ‘the street of ink’ as it was called because most of the national newspapers had their headquarters there. And I attended the London School of Printing as it was known then.

Eventually in 1963 I finished my apprenticeship and was released to be a journeyman in the general trade as a fully fledged typesetter, which meant that you could go to work for different employers, gaining different experiences and new design skills.

My first foray into lettering as a business started a couple years later when a fellow student remembered my handwriting. He was working for a photographic typesetting company called Photoscript and they wanted someone to produce a typeface catalogue for them. So he called me up.

How did that go?

I had no idea what they really wanted but I didn’t hang around! I knew a lot about typefaces even then so I wasn’t fazed but when I saw the range of typefaces they were offering to designers, I was blown away. They included obscure fonts from the Victorian period of type design in America like the T J Lyons collection and the hand drawn fonts from Madison Square advertising agencies. It was just amazing to me.

So I set to work on creating the Photoscript tracing sheet catalogue. Because it was pre-computer days, typefaces existed in catalogues, an alphabet on a page that was created and distributed by typesetters to advertising and design agencies and printers. Typographers and designers used to have to trace letters by hand from these catalogues to design the headlines for their ads, magazine articles, book covers – everything.

However Photoscript was so busy doing typesetting for their customers that they had no time to set the type for their own catalogues, so I had to learn to do the photo typesetting, the layout and the artworking process myself. I eventually ended up running the production team so I thought, “I could be doing this for myself in my own business”.

Who were your first clients in sign making, how did you get them?

Brian: It’s funny, there’s a book Tim got me on Biba. Don’t know if you’ve ever heard of them. It was a very famous fashion store in the ‘70s that sort of turned into this design movement. They had the most lovely art-deco interior – look, we did all this work. That was one of the first major contracts that my original company, Alphabet, got – it started with one tiny logo, and then, we did the whole department store in the old Derry and Tom’s building down at Kensington.

How did you get into calligraphy, and given your history, why not signwriting?

Brian: If you asked a signwriter to do calligraphy, he probably couldn’t do it. Ask me to do signwriting, I would struggle because you’re holding something wobbly – a paintbrush, loaded with paint. I’m happy when I’ve got something that’s rigid to work with.

The first thing that I ever remember doing was I wrote on the bottom of my fishing rod. I wrote my name on there as nicely as I could, and I’ve still got it. Then the other day somebody gave me a fishing rod and I thought, “I’ll give that to my son, Tim.” It’s olive green and I wrote on there in white ink and then, I varnished it. It looks really nice above the handle.

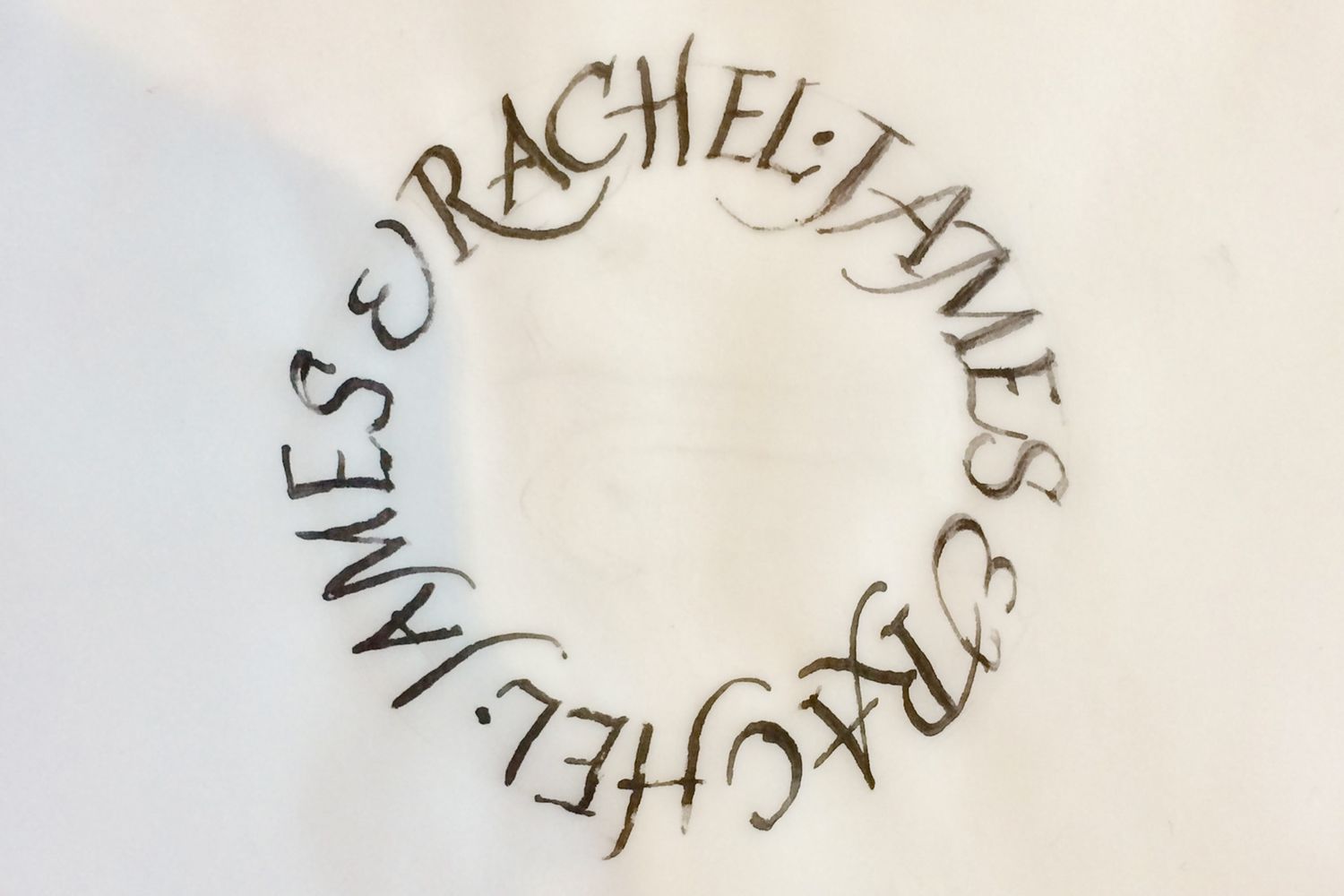

The reason I do calligraphy is that I love talking to people. And everybody likes their name, and if you write their name, you get “Oh, God, blimey, it’s my name.”

I’ve got a mate of mine who works in the post office. I said to him, “I don’t know what the postmen must think when they do the sorting and they see my envelopes come through.” And he said, “They love it.” Because posting letters to people had disappeared really but now it’s coming back – I love personalising things.

So it’s an icebreaker?

Brian: People don’t want to see the stuff that looks perfect all the time, they want something with history, where they can see how something was made, and for me yes, it is an opportunity to talk to people, I find it interesting, you learn things with others. That’s also why I do my guided walks around the historic type foundries of the City of London. There was so much industry within just 300 yards of Glyphics in Leonard Street, near the Barbican area. Teaching people about it puts us, Londoners, in context of where we are now, and I get to talk to people and perhaps learn from them.

Sharon: And you get inspiration…

Yes, how does it inform your work?

Brian: You might not have a project on, necessarily, but you always think, maybe even while you sleep, about how somebody’s done something. I’m just still thinking about that letter shape or the way something worked together – it just kind of lays underneath you. You can’t always remember what you thought but it’s there. Then I get up and go straight to the drawing board, literally. I just like to have a pen in my hand and write until Sharon says, “Come, we’ve got to go shopping.”

Is there a meditative quality to calligraphy for you?

Brian: Yes, it makes me calmer.

Do you have a morning ritual?

Brian: I get up at 7:00, 7:30. Sometimes, it could be 6:00. It depends on what we’re doing. Well, we invariably have music on, don’t we? There’s always music.

Sharon: Yes, you make some coffee.

Brian: Yep. And then, Sharon wakes up-

Sharon: Sometimes, I wake up, and I find he’s got his iPhone, and he’s looking at YouTube people doing calligraphy.

Whose work are you looking at now?

Brian: I would say there’s a guy called Tom Perkins who is a letter-carver, but he’s also a calligrapher. He designs typefaces, and his wife, Gaynor Goffe, is excellent.

Sharon: He carved you a rook.

Brian: Yes, you see that above the top there. He did that for me. Then there’s this guy, Denis Brown. He’s very, very good. He’s an Irish calligrapher.

Sharon: Paul Antonio.

Brian: Yes there are several people. They all have skill with the pen and like to share their skill.

Do you think art, in a way, is a form of narcissism?

Brian: I suppose it is. The funny thing is sometimes when I’m out looking at other people’s work, I think, “Why does their lettering look better than mine? What are they doing? Is it height of the capital letters compared to the height of the rest? Is it the consistency of slope?” I think, “It’s like my writing, but it’s kind of not like my writing.” They’ve got a kind of flow to their work – I think that comes with confidence. It’s the inside coming out so it’s natural to have that sense of exhibitionism

Sharon: And you’re over here working in isolation, aren’t you?

Brian: Yes. So ego is kind of quite important, it pushes you to practise.

Are you competitive, do you think?

Brian: No.

Are you driven by perfectionism?

Brian: The thing is, in my mind, my standards are higher. Yet, to other people, they’ll say, “Oh, that looks nice.” I don’t want it to be nice. I want it to be, “Oh, Christ, that’s bloody brilliant!” I think, sometimes, the ability is not as good as my thinking – working with a pen is actually quite hard, and it’s like any of these things. The more you practice, the better you get at it.

So yes. I suppose I am. I’m competitive in sport. I like winning. You want to be better all the time. Yes – I think I’m actually quite competitive. I think I’ve always been like that ever since, because I started my first business when I was 20 … Tim was born in 1965. He would’ve been three or four when I started the first business out, so I had to be.

Is there anything interesting you’re reading right now?

Brian: No, I used to be a really prolific reader. I used to work in a library, but they were not normally fiction books. They were books on anything – shells, rocks. It could be any bloody thing. And then, all of a sudden, at some point, I stopped reading. Now I’ve got loads of books but I’m not necessarily reading the stories –

Sharon: But you’re in there, learning about other artists’, calligraphists’ work.

Brian: Yes I like to absorb information. I tend to read the newspapers a lot. I’m interested in scientific discoveries, genomes and medicine. I like archaeology too. And I think, sometimes, you get inspiration from that, as well. There’s a weird thing that happens when you read things – you build a background knowledge, and in some subconscious way that does influence your output.

Do you ever feel blocked? How do you deal with it?

Sharon: You don’t seem to have a mental block. I’ve got a cupboard full of art materials, and I find it really difficult to actually get a piece of paper out –

Brian: And start.

Sharon: … and do anything. Whereas, Brian, he doesn’t have a fear of a blank piece of paper, do you?

Brian: No, I don’t think so.

Sharon: And you’ll pick up an old newspaper to write on. And you’ll draw, write, on any material in a café, whatever.

Brian: On the serviettes. Anything. I just write. Yes, that’s funny, though. It’s never really scared me at all – I don’t waste paper. If there’s newspaper about, that is a piece of paper and I’ll be using it for testing a bit of colour out on, or I’ll scribble in Biro to try to get that scratchy texture.

So I find paper quite valuable – but I think you’ve got to break the mould. You’ve got to get a line down. You’ve just got to get a line down, and then ask, what is this? Only a piece of paper. Valuable as it might be, but it’s only a piece of paper. You could always rub that line out. I can always draw that letter again.

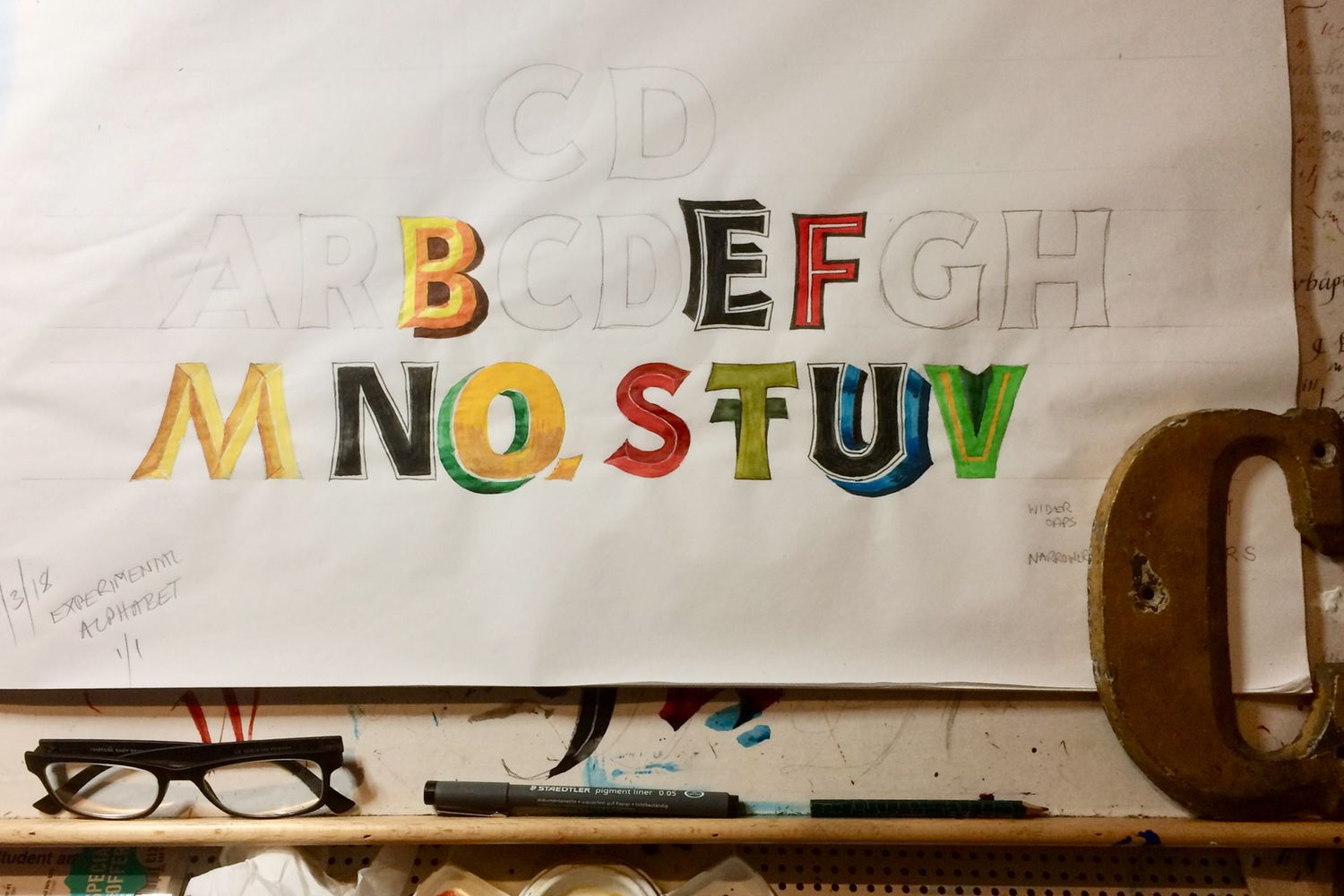

How many types of script have you mastered?

Brian: Probably three – one of them is Copperplate which is a type of traditional English Round-hand, one’s italic handwriting which is sort of semi-cursive, and then there’s another one, Black Letter. If you had a word like ‘lagoon.’ You imagine something lazy, so you just write letters the way the word sounds – in this case, in a spaced-out way. It’s amazing what you can do, but yes you end up probably using three styles or variants of theese.

I do experiment sometimes as well, I’ll take a Coca-Cola can and make a pen. I cut out the metal to make a kind of scimitar shape, and just fold it over into a stick. And then I dip it into my ink. The ink is actually held up by the fold of the metal, and you can sort of swirl it around, and you get splatters coming out of it. Weird things like that. So, it’s a letter shape but not a script you’ll recognise, it’s these interesting jagged lines that you can imagine on a film poster for some dark movie. You can take virtually anything, like a plastic knife, to a broomstick, if you’re going really big scale.

What’s the highlight of your career been so far?

Brian: I retired at 75, so after 60 years of working. You meet and do so many things. You can’t remember all the things that you’ve done. But it’s been brilliant, really, because all the people and artists that I met and worked with in lettering - they were all lovely...just doing a job.